What's Up With WorldCat?

This piece was originally intended for submission to one of several academic/technical library publications as a “communication.” However, in February 2023 my family experienced two overlapping crises which occupied much of my mental and emotional energy for the next 6 months. I let this piece slide in favor of more critical work. Since we are approaching the 2-year mark of this release and the piece is no longer timely, I don’t think it has much value for the original venues. But while not timely, I think it’s still relevant. We also have more statistical data than we did at in February 2023.

I’ve reviewed and added a few observations that I would not have included in a formal publication. I have also added statistics from Fall 2023 and footnoted things which appear to have changed but were present in February 2023.

When not otherwise specified, searches were performed and screenshots taken between January 17, 2023 and February 9, 2023.

“What’s Up With WorldCat?”: Assessing the New WorldCat.org

For more than 15 years, WorldCat.org has been the world’s largest public aggregator of library records.1 While the best-resourced academic libraries also pay for enhanced OCLC products, such as FirstSearch’s more advanced searching of the same data or local WorldCat Discovery instances, many of our own researchers choose WorldCat.org instead. We support them by providing interlibrary loan (ILL) links and other configurations which smooth their path from discovery to delivery.

So it mattered when, on the first day of the Fall 2022 semester, librarians came into work to find that OCLC had launched a new WorldCat.org interface overnight. Many of the changes were aesthetically pleasing, but core functionalities had changed or gone missing. Adding to the normal confusion of a site update was a complete breakdown in locations.2 This affected everything from the list of nearby libraries to IP-range detection. On top of everything else, our ILL request links had disappeared. We didn’t know if we needed to update configuration, if it was a side effect of location errors, or if ILL integration was just gone.

By mid-September, OCLC’s team had fixed the locations issue and helped me restore our ILL link. With Fall 2022 and those launch day bugs in the rearview mirror, it’s a good time to look through the major changes. What’s different and how’s it working? For length, I focus on the primary use case for WorldCat.org in academic libraries: locating and requesting materials.

Searching and Results

Because the old site did not remain online, I was unable to meaningfully compare search between the two systems. Facets remain essentially the same with the improved option to refine using date ranges, previously only available in the Advanced Search. Search uses the same field-specific index codes such as ti:, au:, se:, and no:. For example, search for ti: harlem unbound au:Spivey, Chris, finds the 2017 and 2020 editions of that work. Links to saved searches should continue to resolve.

Sort by Date

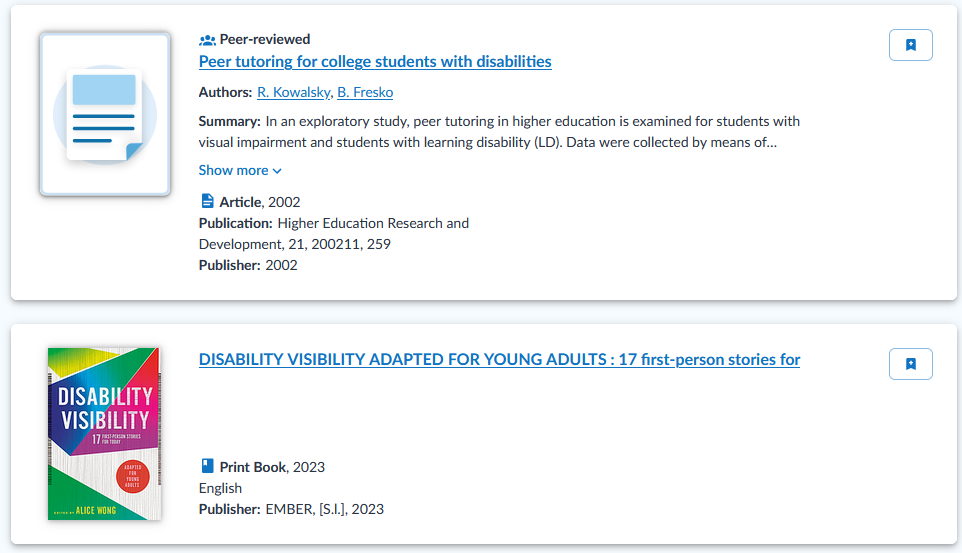

Sorting search results by date3 is complicated by the inclusion of articles from journals and newspapers in those results. When searching for Alice Wong’s Disability Visibility, I found that when ordering by Date (Most Recent), the top result was a 2017 Sydney Guardian newspaper article about disability rights. The next four results were also articles: two from 2022, one from 2016, and one from 2002. One might expect errors if the articles didn’t have dates; in this case its cause is less clear.

Example of 2002 article sorted above 2023 book

I reproduced this issue across several searches. Because I could not do sustained side-by-side testing, I cannot be sure whether this issue is due to the inclusion of more articles or simply more visible due to the amount of screen space taken up by a single result.

A solution is to limit one’s search by format. After I selected Format: Book, my most recent result was a soon-to-be-published adaptation for young adults (the work I was seeking).

Access and Request

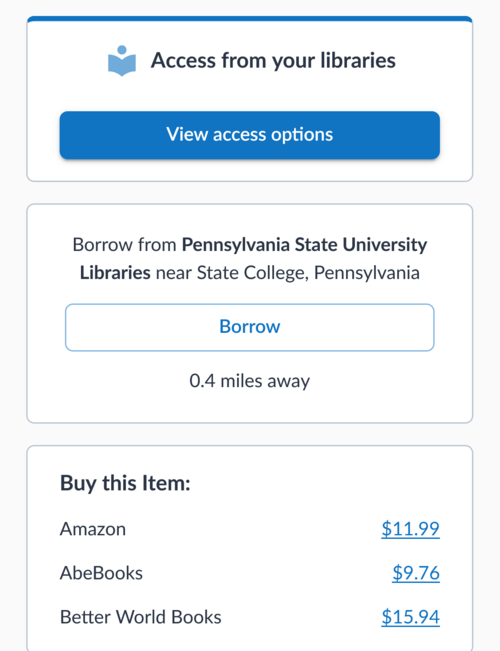

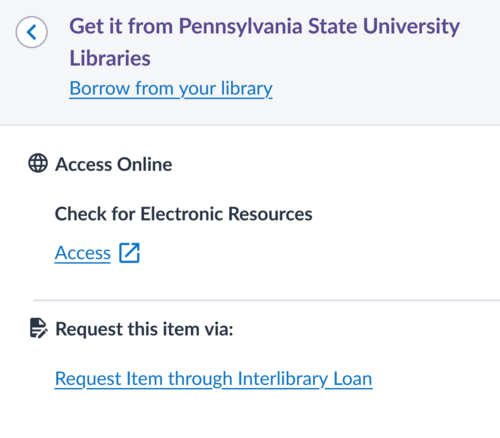

In desktop view, the primary boxes for accessing and requesting materials display in the right sidebar of a resource page, above links to buy the work at Amazon, AbeBooks, or Better World Books.4 The mobile layout uses a single column, placing these boxes in one’s path directly below a work’s summary.

Mobile access, borrow, and buy options

One area for improvement is the display of a Catalog link in the “Access from your Libraries” box shown below. While at the top, the link is less prominent than other sections, particularly in the desktop view. The styling choices make it appear more like a header than like an option users are supposed to consider.

Access options on mobile

Access options on mobile

Access options on desktop

Access options on desktop

I brought this up during my September 15, 2022 meeting with OCLC WorldCat.org representatives, but it has not yet been resolved.

Unavailable Ebooks

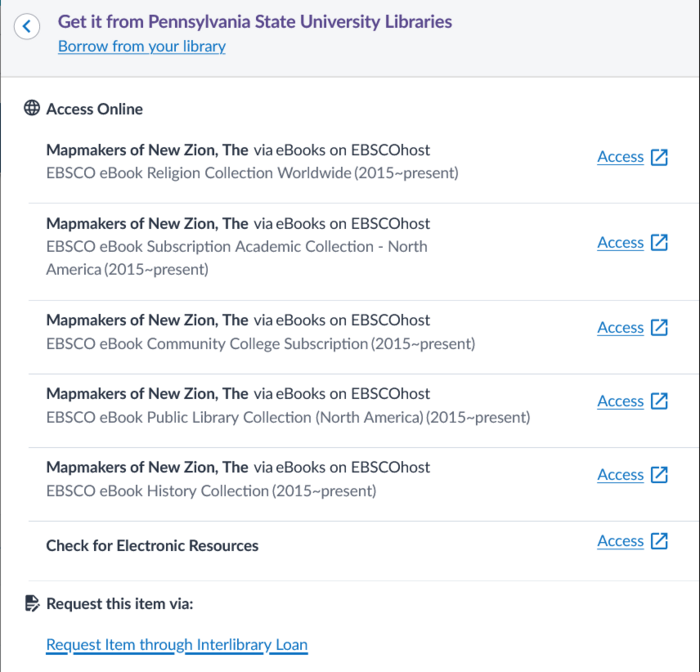

More perplexing, however, is the inclusion of ebook links to EBSCO. This is particularly evident on records where a link to every possible package is provided. At the time this screenshot was taken, we did not subscribe to a single one of these packages. Even if these were accurate, it would be an abysmal user experience. Two e-resource librarians I spoke to at other academic libraries discovered the same problems on the same records.

Example of EBSCO Links

Example of EBSCO Links

After some troubleshooting over Zoom with one of these librarians, we found that OCLC’s WorldShare Collection Manager had inaccurate holdings information about our EBSCO subscriptions. Data sources can be configured in Institution Settings > Knowledge Base Data > Data Sources. After some discussion about the level at which we could adjust these settings, we both left them as-is. We have both learned through bitter experience that it’s actually impossible to get EBSCO/ProQuest/OCLC to share accurate and synchronous information with each other, but we didn’t want to lose any correct links either. We manually deactivated a number of packages instead (in an amusing twist, my library did get access to some of these packages through a PALCI program in Summer 2023).

The “Check for Electronic Resources” link populates a request in our ILLiad. Not the most accurate label, but I’m glad our folks are being sent to a place that might actually work for them.

Catalog Linking

I tested about a dozen “borrow from your library” links to our own catalog and several “Borrow” links for other libraries. The quality of these links has neither improved nor degraded. They remain dependent on whether the primary identifier from WorldCat.org matches up with the identifier in the library’s system. Unfortunately, this is not always the case, due to timing of WorldCat updates, merges, and record overlays. Unfortunately, without a significant system redesign or reclamation project, this is outside any of our control.

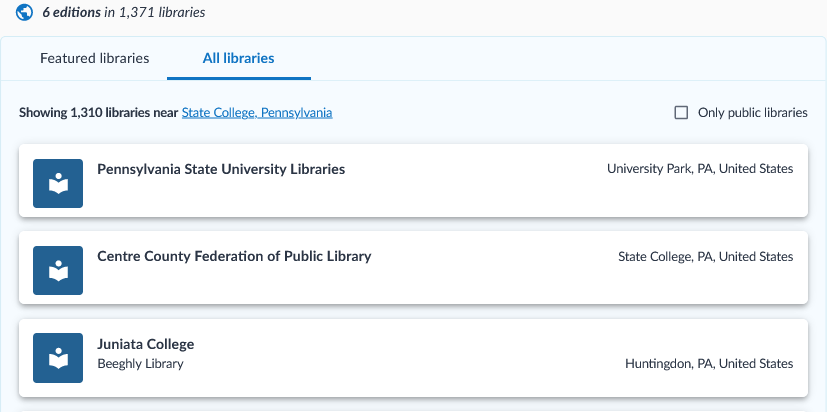

Holdings: Tiered and Expanded?

One notable change in holdings display is that they are now divided into: Featured and All libraries. All libraries lists library names with city location. But there is nowhere for the user to go next. Links to these libraries have been removed. This is an informational dead end. I expect that mobile users are particularly likely to be frustrated, as users conducting research using on a laptop or desktop can easily open another tab. Mobile’s convenience relies on linking and flow, which this interrupts.

All libraries (Desktop view)

All libraries (Desktop view)

The holdings section highlights the tiered nature of WorldCat. In order to become a Featured library, one must pay for an OCLC Web Visibility subscription or have a package which includes it.5 Costs are not published, but one community college librarian reported a quote of about $2000/year.6 With even the best-resourced libraries facing massive budget cuts, adding a new subscription is unlikely to be feasible for small institutions.

New or Not?

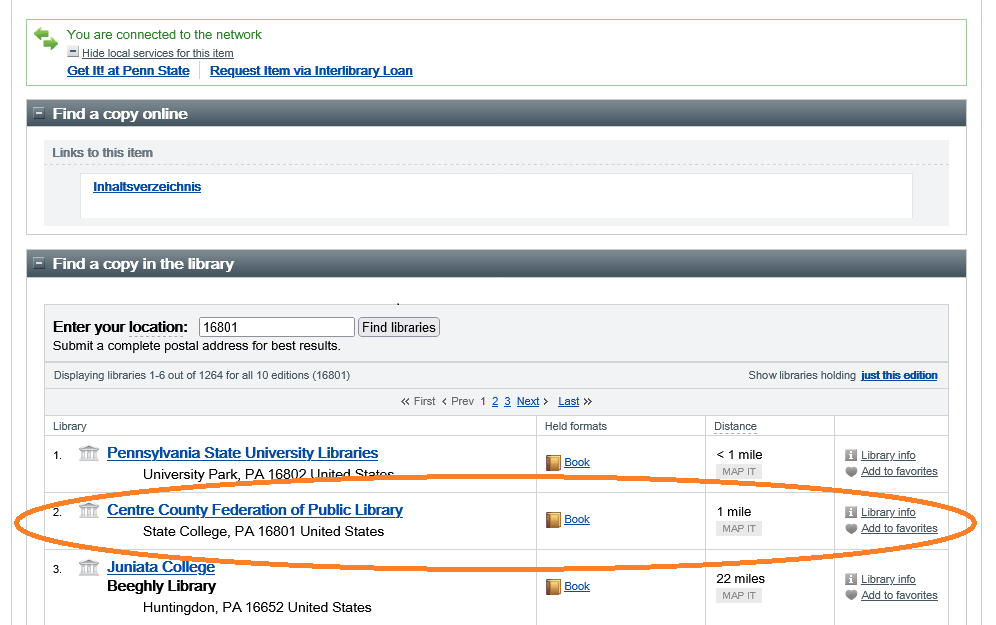

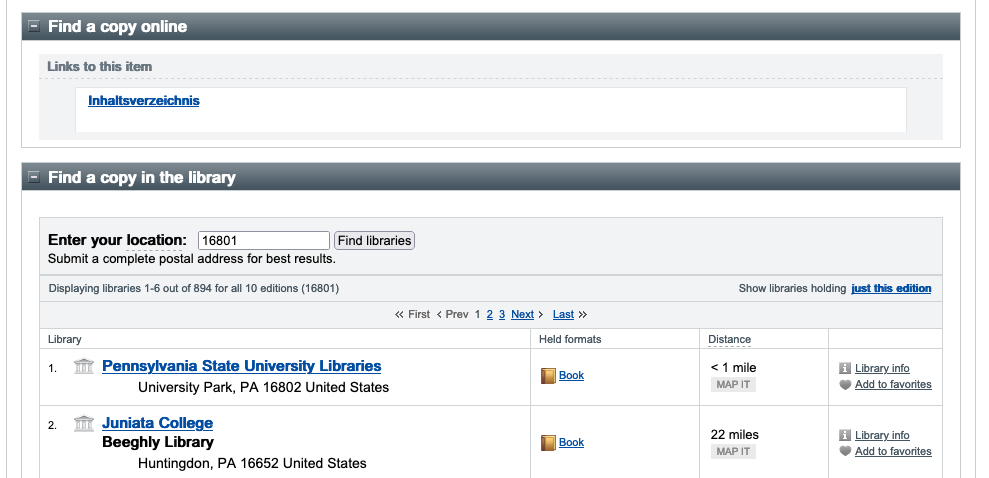

One point of confusion around the launch was the assertion from OCLC that non-Featured libraries were previously not shown at all. Librarians swore across Twitter, Facebook, listservs that we’d just seen those same libraries listed and linked in results. I found the answer on September 19, 2022 while experimenting on worldcat.org.nz, where the old interface was temporarily available.7

Using our institutional VPN, I not only saw my non-featured public library in the results but the listing linked to an identifier-based search of their catalog. This more closely paralleled our FirstSearch results. From my home IP, results matched those in the new Featured libraries. Therefore, for FirstSearch subscribers, the change degrades the usability of results.

Results when on Penn State’s VPN

Results when on Penn State’s VPN

Results when on home internet

Note: I think every library should be linked for everyone, not just FirstSearch subscribers, and these screenshots prove that such links can exist and existed until very recently.

Featured Holdings: Ongoing Improvements and Useless Sidetracks

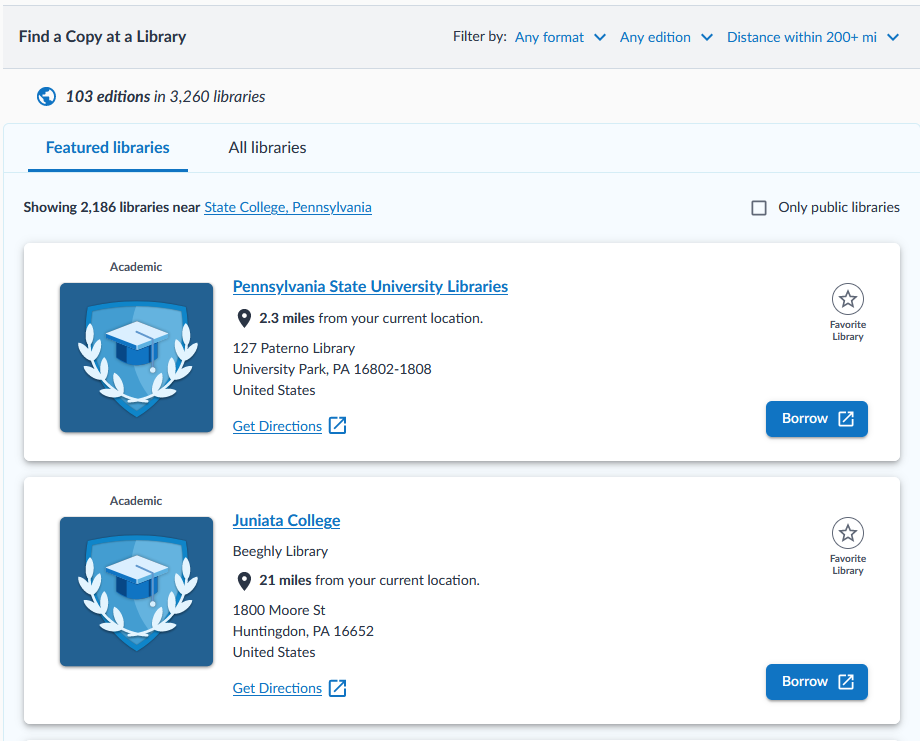

The listings under Featured libraries have been improved in several ways since the launch. Initially, much of the space was taken up by generic thumbnails and multi-line addresses—not especially valuable information. When providing feedback to OCLC, I also noted several choices that directly contradicted well-established principles of web design.

While mobile users saw a prominent Borrow button, desktop users saw the box’s most useful link on the bottom right side of the box. For cultures which read left-to-right and top-to-bottom, our eyes’ scanning patterns look in this location last. If the Borrow button were the only actionable item, this would not necessarily have been the wrong design choice.

However, the holding library’s name was shown in the top left and most prominent location and linked. Contrary to user expectations, clicking this link lands one on an internal WorldCat.org page with information about the library. The book was nowhere to be seen. This caused particular confusion because linked names had previously continued one on the path to acquiring materials in the library’s catalog.

Original featured libraries layout

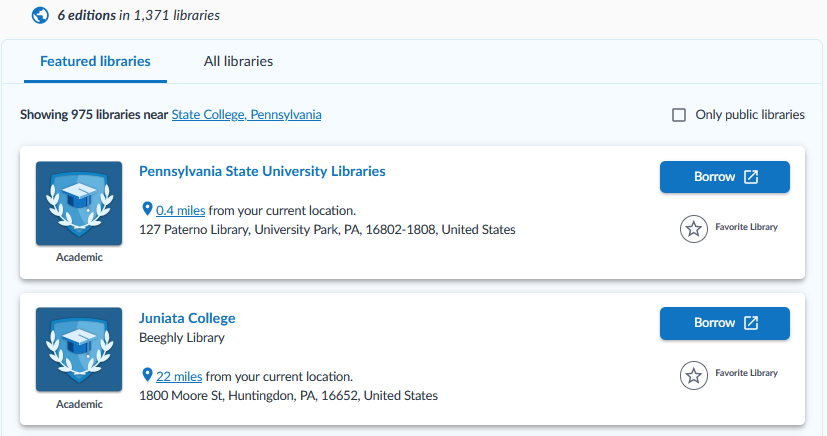

A release in early February 2023 made several improvements. Icons8 were smaller, addresses now take up only one line on desktop and, critically, the Borrow button had now moved to the top right of the box, closer to best practices while still a second-fiddle to the WorldCat.org library page. These changes also reduced the amount of space each box takes up on the screen, allowing one to quickly scan through and use these results.

Updated featured libraries layout

Updated featured libraries layout

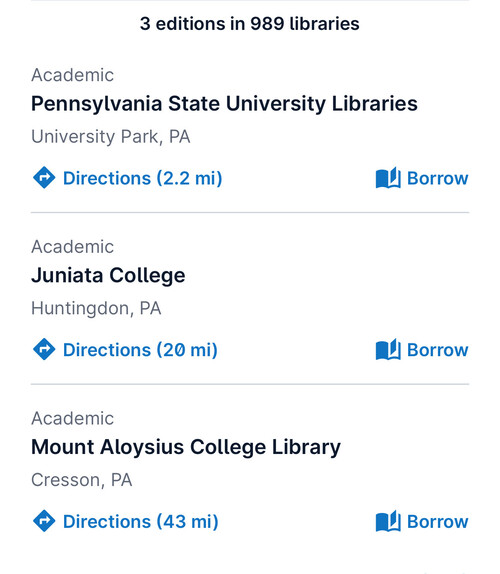

Alternative App-lications

Since the WorldCat.org Find app is completely separate from the site and came out later than the new site, I am not doing a full review of it here. However, I downloaded it to compare elements of concern. Most notably, its featured library display does not include extraneous links or take up extra screen space with repeated icons or addresses. The actionable Borrow link is visible and usable.

Screenshot from August 2024

Screenshot from August 2024

The app’s developers also resisted adding unclickable listings. When I look for Disability Visibility, even if I filter to public libraries, I cannot see that my local public library has a copy.

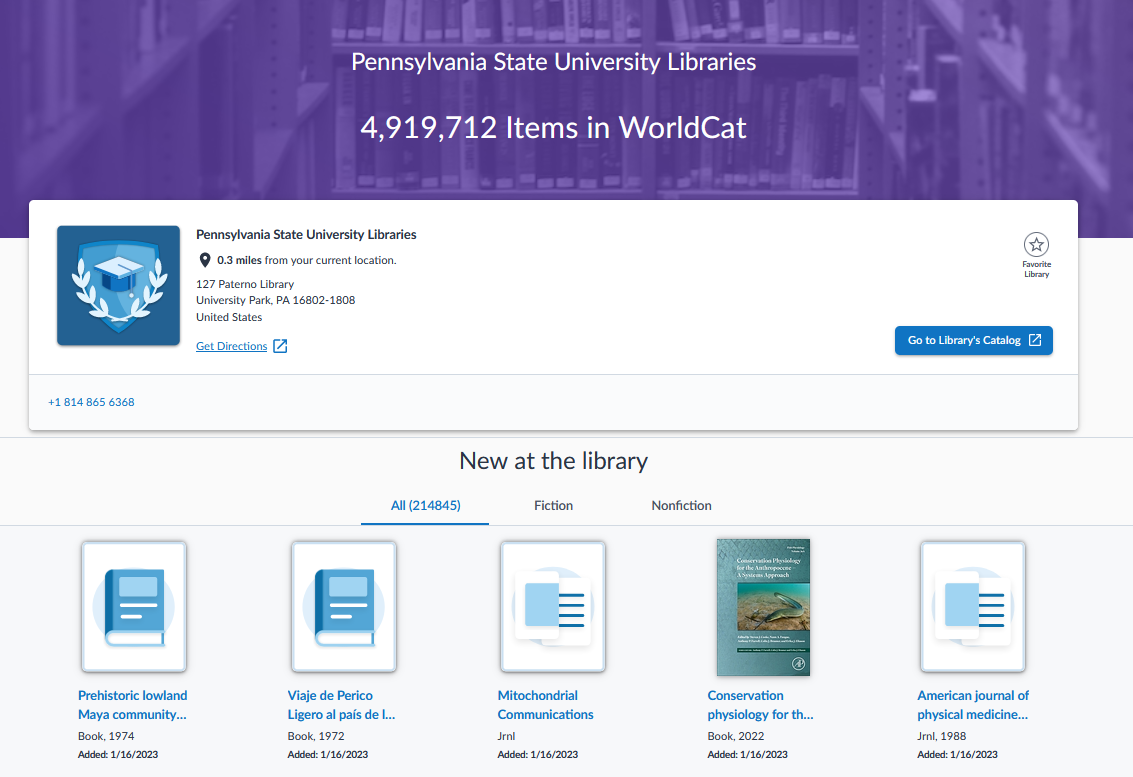

Library Pages: Sidetracks to Dead Ends

The link for a library’s name still takes one to the WorldCat.org page for that library. Pages repeat the library’s address, link to its catalog, and display its most recent WorldCat holding updates. There is no search box. Scrolling through them may be a little fun but isn’t productive for the person who had been trying to get their hands on materials we hold.

Penn State’s WorldCat.org library page

Penn State’s WorldCat.org library page

It is unlikely a person looking at holdings would pivot to learn more about the library. It is more likely that those who end up on this page thought they were continuing to the library’s catalog, even if they don’t know the term. For those who do want information about the library, any library’s website provides the same information along with time-sensitive details, such as special hours and announcements.

A cynic might suspect that this was intended to increase metrics such as pageviews per session and session length.

Addresses: Unreliable for Complex Systems

Addresses in WorldCat.org have always been unreliable. Larger systems, my own along with most public libraries, frequently assign holdings data in WorldCat at the system level. Many of our resources are not at University Park but may be at one or more campuses around the Commonwealth. It would be a monumental task for catalogers supporting a dozen or more libraries to maintain that data, especially when many branches may hold a copy of a work.

Addresses also don’t matter much until one knows if the item is on the shelf, which requires checking the catalog. Reducing the amount of space these take up is at least an improvement from the launch.

Traffic

In promoting visibility subscriptions, OCLC promotes them as a service connecting users to our libraries and materials. How well does the new WorldCat.org do this? The table below shows how referrals to our Catalog (from Matomo) compare between fall semesters9 2020 and 2021 (old WorldCat.org) and 2022 and 2023 (new WorldCat.org). The first two months of Fall 2022 and Fall 2023 suggest that either WorldCat.org usage overall is down or fewer users were clicking through. We always expect lower numbers in November and December, but this still seems like a decline.

| Month | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| September | 1698 | 1545 | 1038 | 1092 |

| October | 1432 | 1602 | 948 | 1051 |

| November | 1087 | 1102 | 910 | 984 |

| December | 1278 | 904 | 834 | 770 |

Table 1. All referrals

Did bounces, users’ decisions to leave the site without navigating to a second page, affect these numbers? Removing bounces, we again see significant differences in the first two months, reaching parity in the second two.

| Month | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| September | 1071 | 850 | 685 | 682 |

| October | 902 | 929 | 644 | 689 |

| November | 674 | 705 | 601 | 654 |

| December | 741 | 542 | 584 | 501 |

Table 2. Referrals with bounces subtracted

OCLC’s Clickthrough Stats

These are the catalog clickthrough statistics they provided us. The first month of then new WorldCat.org is bolded. With locations not being fixed up front, the drop makes sense for September, but then continues.

| Academic Year | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021-22 | 1566 | 2134 | 1999 | 2128 | 1432 | 1215 | 1651 | 1773 | 1911 | 1354 | 1199 | 1732 |

| 2022-23 | 1570 | 1301 | 558 | 899 | 925 | 793 | 1269 | 803 | 935 | 806 | 888 | 734 |

| 2023-24 | 782 | 1254 | 1101 | 1033 | 998 | 770 | 1598 | 1139 | 981 | 1009 | 955 | 801 |

Totals:

- 2021-22: 18,362

- 2022-23: 10,747

- 2023-24: 11,620

Whichever of us is correct, the change certainly hasn’t increased clickthroughs. It’s also worth noting that as of of August 2024, you still can’t access stats for WorldCat.org clickthroughs from the WorldShare Analytics module. In fact, there’s a big banner up there letting you know that you have to put in a ticket to get them.

Interlibrary Loan Referrals

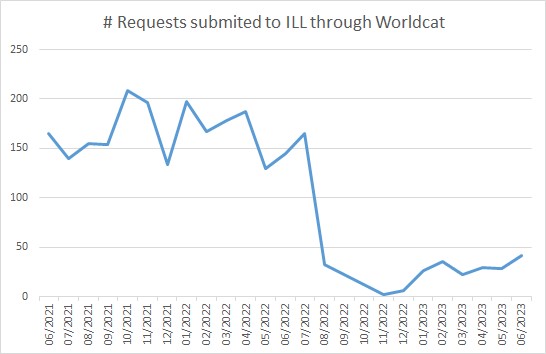

A colleague at UMass Amherst graciously shared their statistics for ILL referrals from WorldCat.org during the 2021-2022 and 2022-2023 academic years. These plummeted after the the new WorldCat.org was released.

# Requests submitted to ILL through Worldcat (2021-2023)10

Library Information Page Referrals

I investigated whether the WorldCat.org’s information page for our library referred visitors and found a negligible 1-4 referrals per month.

Conclusion

While visually appealing, the new WorldCat.org’s functionality leaves much to be desired. There is a real improvement for mobile users, as long as their library pays to be featured. Good thing we live in an era of skyrocketing library budgets and not austerity and library clos…oh. Right. Even those of us who’ve been paying for service have lost linking paths to those catalogs.

When this piece was going to be for publication, I felt that I needed to include something constructive. Checking your settings, ensuring that your library’s information is up-to-date and your Knowledge Base data is as accurate as possible may mitigate some of the downsides. That’s really all I can give you.

Perhaps if OCLC were not paying its CEO two million dollars a year, they could find a few bucks to link to everyone’s catalog, even if the display were still tiered. (Actually, the previous version proves it was entirely possible all along and they could have expanded it to be visible to everyone.)

It’s really about choices. Choices to put internal links in the place that should be linking to the resource. Choices not to even offer search on those internal “library profiles.” Choices to remove links to catalogs of less-resourced libraries for paying subscribers,11 rather than expand them for use by everyone.

After all, that’s how OCLC operates. As their motto goes: “Because what is known must be shared.®” The ® should be pronounced: “if you pay to play.”12

Footnotes

-

It has achieved this both by providing valuable services in library record aggregation which means that it has these records and by legal threats which have ensured that others don’t. Many librarians, particularly catalogers and technologists, have privately (and publicly) alleged these practices to be monopolistic. It also provides services recording library holdings (who owns what) and facilitating interlibrary loans. ↩︎

-

OCLC’s team shared that CloudFlare’s initial settings were locating people at its datacenter sites and had to be updated. Meeting with the product owner and staff member, September 15, 2022. ↩︎

-

As of August 2024 this issue appears to have been solved. The number of articles in results still means that limiting to format is likely going to be useful when trying to locate other materials, but the feature itself works. ↩︎

-

Some librarians posted on Twitter at the time alleging that these were new, but I think this was due to the layout change. While more prominent in the new site, especially in the mobile view, these links were present before the update. ↩︎

-

Described at https://www.oclc.org/en/web-visibility/web-visibility-subscriptions.html. Accessed August 6, 2024. ↩︎

-

Personal communication, September 1, 2022. ↩︎

-

I became aware of this on the 19th and posted about it on Twitter. I’d planned to continue side-by-side testing, but the site had become unavailable by the next day. My bad. ↩︎

-

Perhaps the WorldCat.org team intends to substitute institutional logos for these repeated Academic, Public, and Regional or National images. At time of this revision (August 2024) it’s still a baffling use of valuable screen space. ↩︎

-

Because this was originally written in February 2023, I did not include spring statistics. Unlike those below, these are complicated to obtain and not broken out as part of my regular stat-keeping, so I did not go back when updating and get spring numbers, though I did calculate Fall 2023 for comparison. ↩︎

-

K. Zdepski, Resource Sharing Librarian, University of Massachusetts Amherst. ↩︎

-

I have no problem with my institution and others like us paying for things if that means those things are available more broadly. We put time and budgets into open source projects and open access journals and the like for just that reason. ↩︎

-

Do not actually attempt to share anything OCLC-created or anything they lay claim to or they will sue you or, if you do so anonymously, sue someone else whom they wildly speculate might be you. The chilling effect cannot be overstated as I spent a moment wondering whether they’d try to sue me for irreverantly quoting their slogan. ↩︎