Introducing Discovery Systems

Abstract

This is the text of a presentation I recorded for an IST 616 course at Syracuse’s library school. I was asked to introduce library discovery in 10 minutes, or less, with some focus on how metadata is created and used.

Hello, my name is Ruth Kitchin Tillman and I lead work on discovery at the Penn State University Libraries. Dr. Clarke has asked me to introduce you to discovery systems, including how metadata functions in the system. Because I’ve only got about 10 minutes, I’m going to cover the background and core concepts and give you the grounding to learn more.

So first, what are library discovery systems? In a nutshell, they’re vendor-hosted platforms where our patrons can search for the many electronic resources that a library licenses, generally combined with records from our own catalogs and possibly our institutional repository and digital collections platform. They’re primarily used at academic institutions and government or other special libraries, rarely at public libraries. At Syracuse, you use Summon – which you can access at https://syracuse.summon.serialssolutions.com/ or through some of the boxes in your homepage search results.

The primary discovery platforms on the market today are: Summon, Primo, EDS and WorldShare Discovery. Summon and Primo were bought and developed by Ex Libris, now Clarivate. EDS is EBSCO Discovery Service and, unsurprisingly, owned by EBSCO. WorldShare Discovery is owned by OCLC. While Summon and Primo have somewhat different interfaces, Ex Libris did a major project several years ago in order to create what they call a “Central Discovery Index” or CDI. So, in effect, there are three discovery indexes on the market, CDI, EDS, and WorldShare.

These indexes have metadata records for journal articles, book chapters, book reviews, books and ebooks, newspaper articles, journals themselves, streaming audio and video, digitized materials, and more. I’m going to focus on journal articles today, but everything I say about them applies to the rest of these with minor variations–there are still publishers or services involved in selling packages, creating metadata records, negotiating access, etc. I’ll be using examples from Summon, the discovery system used at Penn State and Syracuse, but what I’m saying applies to discovery as a whole.

Record Packages

To start, where do these records come from, how do they get into the system, and how are they used?

Discovery systems are built off of Electronic Resource Management data. When a library licenses electronic materials at the article level, we often do so through some kind of package deal. Sometimes, they overlap in weird ways, like the Idaho Librarian, which you have from 1998 to 2016 through Library Literature and Information Science Full Text and also 2011 to 2014 through ProQuest Central.

When we select a package in the electronic management system that’s paired with our discovery system, the discovery system already has metadata records for that package and adds them to its index along with our other holdings. We do this for all of our paid subscriptions and we can also turn on things like Directory of Open Access Journals, which provides individual article metadata from thousands of open access journals.

Metadata Records and Sources

So the metadata records are already within the discovery system and we get them by activating the subscription. Who actually makes them and what do they look like?

Many records originate with the publishers but they may also come from databases, which either originally got them

- from publishers,

- from another service,

- or by hiring people to create the records from scratch.

For modern articles, what tends to happen is a bulk extraction and transformation of metadata from the originating journal. For instance, the field in the journal software for the title? That exports to a title field, volume and issue number, etc. In many cases, someone assigns keywords and subject metadata. This might happen in the journal itself, but an indexer may add their own subjects or other controlled vocabulary terms based on keywords. Depending on how the data is stored and who’s providing it, the discovery service may have a full text copy which they index for search but don’t display to the end user.

We send our own MARC to Summon, too, which indexes it based on their understanding of MARC records and configuration we provide.

Sometimes we purchase collections of records for articles to which we don’t necessarily have access but which we commit to getting via ILL–and we still pay the metadata provider for those records.

This all varies widely by publisher, by licensing agreements they offer, and even by how well some vendors cooperate with each other. Sometimes a publisher or even a large database won’t share any metadata with discovery services – so while they’re supposedly one-stop-shops for this kind of search, some things we license simply aren’t present at all.

Before talking about access, let’s look at some records:

While Ex Libris tries to deduplicate when possible, we still sometimes end up with two records for the same thing. These are both records for “‘But a Quilt Is More’: Recontexualizing the Discourse(s) of Gee’s Bend Quilts.”

[Note: these screenshots are composites of the original Quick Look, which is a very long, thin bar on the right side of the screen. The original talk demonstrated this live.]

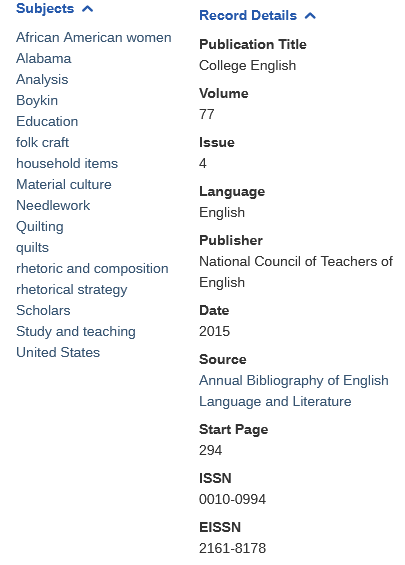

The first comes from the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature:

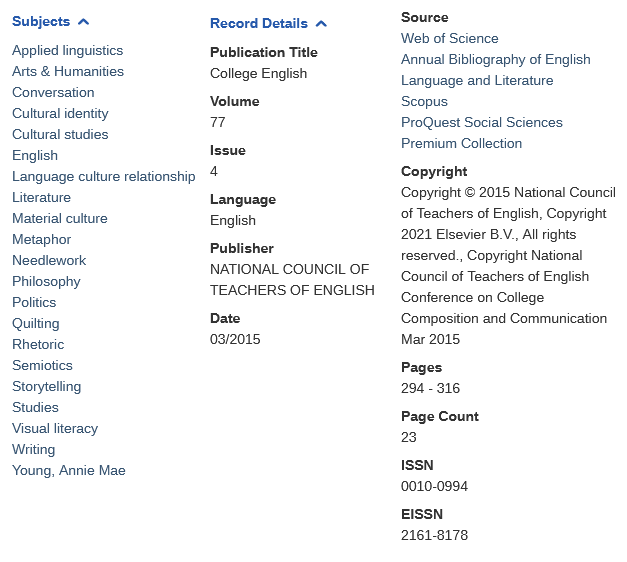

The second comes from multiple collections, including the same bibliography:

I chose this example because while the records have the same title, author, volume, and issue information - the snippets they display and their keyword indexing reflect very different ways of thinking about the content. Some other information like publisher name, page numbers, page count, etc. vary – whether by capitalization or inclusion. These differences, and the apparent presence of both versions in the same bibliography, probably stopped the indexer from identifying them as a duplicate.

Both link to the same article but at different sources.

Access and Appropriate Copies

I’m going to touch for just a moment on the “appropriate copy” problem, which is one of the things early discovery systems were trying to solve. When you have access to an item through several different databases, how should you get it?

Let’s click the links for those two articles.

Article 1 at JSTOR:

Article 2 at ProQuest:

While “link resolvers” are a separate technology from discovery systems, discovery systems tend to integrate a link resolution mechanism. In theory, these should be simple: you click on the link and it finds thing you were looking for, whether you’re looking for an open access article or one that was just published or something from the 1920s.

However, link resolution is also dependent on metadata. If the record has incomplete metadata or a publisher made changes to their site and hasn’t updated URLs, etc., the link may fail. Last week, all of our Kanopy video links broke because of a change on Kanopy’s side, though they restored access later that day. Depending on the kind of failure, the patron might see an error message that allows them to place an ILL or put in a help ticket with us. They might also find themselves on the front page of a journal website or on the journal’s own error page.

Coverage and Complications

The biggest challenge of discovery systems is that of scale. When I’m recording this, for example, Syracuse’s Summon index has over 1.3 billion (that’s billion with a B) metadata records. It’s impossible for anyone to monitor that much metadata–so errors are found and fixed reactively, not proactively.

And unless the metadata is for an item in our catalog itself, there’s nothing we can do to fix it directly. At Penn State, we have an e-resources team with decades of experience, so they’ll try to get a copy for the patron, if possible, using their fuller knowledge of ways to access materials. They’ll then put in a ticket with our vendor explaining the problem experienced. They may also test other articles in the same journal or from the same publisher in order to determine whether the problem is a single metadata record or if the structure for linking to an entirely publisher needs to be changed. Resolution time on these tickets can be a matter of a few days to a few months, which is a difficulty with any vended system–so many things are entirely out of our control.

Then there’s the issue of incomplete coverage. You’ll remember how I said that sometimes a publisher or database won’t allow their resources to be indexed. So when we add a new subscription package to our electronic resource management system, it may let us know it only has metadata records for 60% of what we’re licensing. For the rest, our users will have to go straight to the journal’s website. But even that 60% may not be accurate. Sometimes things break down in the pipeline and they stop sending metadata for new articles, even though they’re supposed to.

Here’s a recent example – we got a note from a graduate student that they couldn’t find articles from recent issues of a journal through Summon. The publisher embargoes it for big groups like ProQuest, so our subscription through a ProQuest package only goes up to 2020. However, because this is a high-priority resource, we maintain a direct subscription to it as well. But for some reason, there’s been a breakdown somewhere between the publisher and Summon. We don’t know whether the publisher has gotten behind on exporting metadata or the problem is somewhere else in the pipeline. Again, all we can do is send the researcher directly to the journal with an apology that they have to add another step to their workflow–and put in yet another ticket.

Conclusion

This is the part where I wish I could tell you not to worry and that there’s a solution underway for all these challenges. But it’s not that simple. In some ways, Discovery systems are a vast improvement over older ways of finding things. They’re also only one tool in your toolbox and knowing when to use them, how best to use them, or what tools you should use instead is part of the skill set you’re developing as a librarian. I hope that you’ll keep all this in mind when using your Summon instance for research, that you’ll ask questions, report issues, and keep learning the best tools to use for different informational needs.